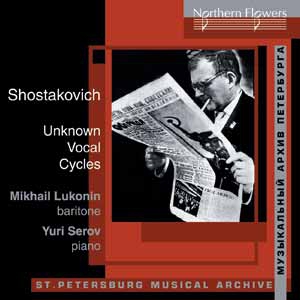

CDs

NF/PMA 9912

Dmitry Dmitrievich Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Unknown Vocal Cycles

Mikhail Lukonin, baritone

Yuri Serov, piano

| ||

1. |

King Lear, music to Shakespeare’s tragedy, Op. 58 (1940)

|

9.32 |

Four Romances to Words by A.S. Pushkin, Op. 46 (1936) | ||

2. |

Renaissance |

2.22 |

3. |

A Jealous Maid Was Weeping Bitterly Reproaching A Lad… |

1.36 |

4. |

Anticipation |

2.43 |

5. |

Stanzas |

5.44 |

Greek Songs (1952 – 1953) | ||

6. |

Forward! (words by K. Palamas) |

2.14 |

7. |

Penthosalis (Folk Song) |

1.37 |

8. |

Zolongo (Folk Song) |

3.38 |

9. |

The Hymn Of ELAS (words by S. Mavroidi-Papadaki) |

1.07 |

Spanish Songs, Op. 100 (1952 – 1953) | ||

10. |

Farewell to Granada (Russian version by S. Bolotin) |

3.40 |

11. |

Little Stars (Russian version by T. Sikorskaya) |

2.03 |

12. |

First Time I Met You (Russian version by S. Bolotin) |

3.33 |

13. |

Ronda (Russian version by T. Sikorskaya) |

1.55 |

14. |

Black-Eyed Girl (Russian version by T. Sikorskaya) |

2.41 |

15. |

Dream (Russian version by S. Bolotin and T. Sikorskaya) |

2.12 |

16. |

The Dawn Is Rising. Words by E. Dolmatovsky From the motion picture “Meeting at the Elbe” (1948) |

1.35 |

17. |

The Counter–Plan Song. Words by B. Kornilov From the motion picture „The Counter-Plan“ (1932) |

2.03 |

18. |

We Had Kisses. Words by E. Dolmatovsky |

1.07 |

| ||

|

The artistic value and importance of theatrical music by Dmitry Shostakovich by far exceed its popularity. The stage life of most of the productions was unusually short, their music had no time to sound and spread, its publications were left on the shelves of theatre libraries and archives, and some of them are lost forever. The music to Shakespeare’s King Lear was the last large work of the composer for theatre (1941, by G. Kozintsev at the Gorky Theatre in Leningrad.) A brochure issued for the premiere of the production contained an article by Shostakovich, which goes far beyond the scope of an author’s preface for a performance: “Shakespeare’s tragedies are amazingly musical in themselves; music is born out of the poetry and dynamics of these tragedies… Every meeting with Shakespeare arouses thoughts that are far beyond the modest task you have set before you. Musical dreams appear, followed by hopes to embody a Shakespearean theme some time.” In Fool’s Songs a tendency to simplify the language of composing is clearly felt, attributable to theatrical production conformities. Nevertheless, the individuality of a unique master shows itself in the dramatic sculpture of images, in the animated vocal intonation. The Shostakovich style is identifiable and inimitable, be it majestic-scale symphonic opuses or tiny theatrical sketches.

Four Romances to Words by A.S. Pushkin as a tribute for the 100th anniversary of the poet’s death (January 10, 1937). Shostakovich had conceived a large string of twelve romances, but never fulfilled his plan completely. The notorious article “Chaos Instead of Music” published in the newspaper Pravda in January 1936 and containing a negative official judgment on the opera Lady Macbeth of Mzensk District, with ensuing persecution of the young composer, made that period in life unbearably distressing for Shostakovich. His addressing of Pushkin, of Pushkin’s harmonious, wise, and classically perfect poetry was a kind of creative ‘refuge’. Moreover, it enabled the composer to speak out on the aims of Art, and on eternal questions of Life and Death. The poem selected for the very first song in the cycle is, significantly, Renaissance. “A barbarous painter may stain a genius’s picture / With his lazy paintbrush” is a clear response of the composer to all the barbarously unjust and unfair criticism that crucified Shostakovich in 1936–1937. For the first time vocal music became for the composer not just an instrument of lyrical utterance, but also an instrument of direct dialogue with the rulers and his fellow musicians who had betrayed him.

In the Fifties, Shostakovich eagerly worked on arrangements of traditional songs, which is witnessed by his several choral cycles of Russian songs, as well as Spanish songs and Greek Songs for voice and piano. The composer definitely sympathised with heroes of the Greek Resistance; this can be heard in the manly and sincere intonations of the arrangements themselves, the tunes for which were sung to the composer by M. Beiku, a Greek woman who lived in Moscow at that time. All the pieces in the cycle are closely related to the history of Greece full of dramatic events. The song Forward is a battle hymn of Greek guerrilla warriors, Penthosalis is a Cretan folk dance, and the tragic Zolongo was sung as a memory of the deed of Greek women: surrounded by Turks on Zolongo Mountain, they dived into the abyss with their children so as not to be captured by the enemy. This peculiar four–part opus ends in the most popular song of the Greek Resistance, The Hymn Of ELAS.

Starting from Glinka’s Jota aragonesa nearly all the great Russian composers were happy to use Spanish tunes in their compositions Musicians of the northern land were attracted by hot rhythms and mellow harmonies of the south Moreover from the mid thirties the theme of Spain became a topic of the day in the Soviet Union its volunteers went to help Spanish Communists in their fight against Franco s regime its newspapers published supporting articles and letters numerous poems and songs were composed and even chocolate factories were given Spanish names.

After the defeat of the resistance many Spanish orphan children were taken to Moscow In the fifties singer Zara Dolukhanova the first and still unsurpassed performer of Shostakovich s From Traditional Jewish Poetry cycle heard from one of such young men some charming traditional Spanish songs full of nostalgia for the lost homeland and of passionate lovers vows The singer handed the recorded tunes to Shostakovich and in 1956 he adapted the melodies to create a collection which he entitled Spanish Songs.

The composition came out warm subtle and fragrant the piano support is transparent and neat. The cycle immediately became popular both with audiences and performers And although the material initially handed over to the composer did not include proper translations (they were revised and improved during the entire work at the songs) while Shostakovich himself had to adjust scattered lyrics to the traditional tunes the opus is amazingly organic in matching typically Spanish melodic and rhythmic patterns with words on love and separation suffered losses and enjoyments of the first love that are so close to Russian soul and so common for the Spanish tradition in Russian culture.

Shostakovich wrote the soundtracks to more than thirty motion pictures, comprising several dozens of songs. Of these, many have not been published, and of those published, not every one seems interesting to today’s listeners and performers Still, a complete edition of vocal compositions is unthinkable without a few most symbolic examples of his film music. Orders from film studios provided means of support, dealing with prominent film directors was an interesting intellectual experience, and working in the soundtrack business helped to refine composing workmanship. Moreover, the sound cinema era was just in its beginning: Shostakovich was on the very frontline of a new art.

The Dawn Is Rising written by Shostakovich to lyrics by Eugene Dolmatovsky for the ‘war’ motion picture, today among the ‘old gold’ of the Soviet cinema was the first experience of joint work of the compose and the poet. Researchers of the Shostakovich music ask many embarrassing questions concerning their long–time and efficient creative alliance. The two men were too much different in their artistic career, scale of talent, and relations with the rulers. But nevertheless, Shostakovich clearly was not annoyed getting in touch with plain lyrics of Dolmatovsky. Apart from the need to be ‘simpler’, to make music comprehensible for broad masses of Soviet listeners, the composer addressed the poet’s lyrics over and over again primarily due to strong mutual affinity that united them. Moreover, Dolmatovsky responded to the composer’s wishes knowingly and professionally, and in his turn offered him up-to-date lyrics for quick musical realization and distribution. The song lyrics nicely ‘fitted in’ with the music, and their contents, their message were in line with the song tradition and the topics of the day. Recalls Eugene Dolmatovsky, “We were young and active, I adored Shostakovich and tried to be of help to him. Sometimes he wrote music crouched over a small table in my flat, amidst noise and fuss; nothing seemed to trouble him. His sharp notation signs appeared amazingly fast. For war films close to me as a veteran, we made much more music than was ordered; we did not spare effort. Life and work were a pleasure.”

The Counter–Plan Song was composed for the motion picture “The Counter-Plan” in 1932, when the composer was finishing his work on the opera Lady Macbeth. Shostakovich had already had experience of music-making for three sound movies. But this was a special case. The film on the labor enthusiasm of Soviet workers needed an up-to-date mass song addressed to an audience of millions. It was to be a Song of the Generation, a Song of the Great Times. There were no models to support the effort. The lyrics were ordered to Boris Kornilov, a young man of twenty–five, the age of Shostakovich himself. He was a self–educated poet who had arrived in Leningrad from Russian backwoods.

The film’s director Sergei Yutkevich wrote in 1977, “Dmitry Dmitrievich found the song at once, he did not offer versions, he accepted and played it in full — the only one we needed.” As a matter of fact, and the composer’s numerous sketches confirm that, the tune of The Counter–Plan did not appear in a moment; Shostakovich re-wrote it several times, striving for agility, springiness, and pliability.

They began to sing this song already in the studio room, during the synchronous recording of the music. Audiences hummed the tune walking out of the hall after each show. A few months after the film release, the song was launched as a record, it was continuously played on the radio, and its popularity was immense. Shostakovich, who seldom commented on his own works, said, “In the end this tune lost its author, and that’s a case the author may be proud of.” The song was immediately translated in many languages, and was performed in Czechoslovakia, Poland, France, Japan, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA. In 1945 it was performed, to adapted words, in San Francisco as the anthem of the new-instituted United Nations. For a few after–war decades, The Counter-Plan Song by Dmitry Shostakovich was an attribute of any official Soviet celebration, and was sincerely loved by millions.

Shostakovich did not specify in his autograph the date of composition of the romance We Had Kisses to words by Eugene Dolmatovsky. The song, however, may definitely be referred to the period of the Fifties, when several significant works were written to words of Dolmatovsky vocal cycles, an oratorio, soundtracks to films. In 1956, the fifty-year-old composer suddenly got married for the second time. His young wife, a former Young Communist executive, soon got accustomed to the soft character of Shostakovich. So one day she praised songs by Solovyov–Sedoy (a most popular songwriter for masses) and added, “Would be great if you, Mitya, also wrote a song or two like these.”

Why, he was able to compose such songs too.

|

Fool’s Songs from the Music for King Lear Words by William Shakespeare | ||

|

|

|

| ||

1. |

|

|

Greek Songs | ||

1.

Forward! |

|

|

Spanish Songs | ||

1. |

|

|

| ||

The Dawn Is Rising |

|

|