CDs

NF/PMA 9925

|

1888–1890 |

|

|

1. |

From Hafiz (Don’t be lured by warlike glory…) |

|

2. |

The Belle. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

|

Two Songs to Words by A. Pushkin, op. 27 |

|

3. |

Oriental Romanza |

|

4. |

Song (Why do I not hear the roar of joy?…) |

|

|

1898 |

|

5. |

5. The Muse. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

6. |

From Petrarca (We Used To Live At The Foot Of A Hill…) Russian version by Ap. Korinfsky |

|

7. |

From Petrarca (When Your Eyes …) |

|

8. |

You Want To Love … Words by Ap. Korinfsky |

|

9. |

Delia. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

10. |

The Sky’s All Silver … Words by Ap. Maikov |

|

|

Six Songs, Op. 60 |

|

11. |

The Grace Cup. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

12. |

Desire. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

13. |

The Nereid. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

14. |

Dream. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

15. |

My Life Is Still Before Me … Words by Ap. Maikov |

|

16. |

Near The Land Where Golden Venice Reigns … Words by A. Pushkin |

|

|

1900 |

|

17. |

Hey You, My Free Song! A Duo. Words by P. Seversky |

|

|

1905 |

|

18. |

Masha Is Told Not To Cross The River. Words of a traditional Russian song |

|

|

1916 |

|

19. |

Shakespeare’s Sonnet LXVI (“For Restful Death I Cry…”) |

|

20. |

Nina’s Song. Op. 102, from the music to The Masquerade, a drama by M. Lermontov |

|

|

Young years |

|

21. |

Stifling! Words by H. Heine; Russian version by N. Nekrasov |

|

22. |

Spanish Romanza. Words by A. Pushkin |

|

23. |

Whenever I Hear Your Voice … Words by M. Lermontov |

|

24. |

My Songs Are Venomousv… Words by H. Heine, |

|

|

1881–1885 |

|

25. |

To Your Snow–White Bosom… Words by H. Heine, |

|

26. |

The Nightingale. Words by A. Koltsov |

|

27. |

When I Look Into Your Eyes. Words by H. Heine, |

|

28. |

Arab Melody. Words from a traditional song |

|

29. |

Spanish Song. Words from a traditional song |

|

|

Total time 67:04 |

|

Providence proved to be extremely benevolent to Alexander Constantinovich Glazunov. He was born in 1865 into the happy family of a well–known Petersburg book publisher, in a large and cozy house, with his parents’ love and care around him. He was endowed with a remarkable musical talent, and a phenomenal memory and ear; abilities glorified in lots of tales and jokes retold by several generations of Petersburg musicians. Thanks to his mother, his gift was noticed very early. The renowned Mily Balakirev and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov became his teachers. At the very outset of his creative career, he was greatly encouraged and funded by Mitrofan Belyaev, a timber businessman, passionate music lover, and one of the most important Russian patrons of art.

The First Symphony written by Glazunov at the age of 16 (after 18 months of studies with Rimsky–Korsakov) and performed on March 17, 1882 during a concert of the Free School of Music under Balakirev’s baton, impressed the audience with its clarity, well-finished form, and easy utterance. In his review of the premiere, Cesar Cui commented that the young author “is a composer fully equipped with talent and knowledge”. The composer himself shyly came out to bow in his na?ve tunic of a secondary school pupil. The same year, Rimsky–Korsakov conducted the symphony at the Industry & Arts Exhibition in Moscow. Through efforts of M. Belyaev and Franz Liszt, the opus was performed in Weimar in 1884, which started to promote Glazunov’s recognition abroad.

Inborn modesty, reserve, unaffected manners, unusual diligence and responsible attitude to professional composer The First Symphony written by Glazunov at the age of 16 (after 18 months of studies with Rimsky’Korsakov) and performed on March 17, 1882 during a concert of the Free School of Music under Balakirev’s baton, impressed the audience with its clarity, well-finished form, and easy utterance. In his review of the premiere, Cesar Cui commented that the young author “is a composer fully equipped with talent and knowledge”. The composer himself shyly came out to bow in his na?ve tunic of a secondary school pupil. The same year, Rimsky–Korsakov conducted the symphony at the Industry & Arts Exhibition in Moscow. Through efforts of M. Belyaev and Franz Liszt, the opus was performed in Weimar in 1884, which started to promote Glazunov’s recognition abroad.s work, honesty, and willingness to help - these personality traits of Glazunov made his name a kind of moral purity standard in the musical world of Petersburg and Russia. The years of his directorship at the Conservatoire of Petersburg (Leningrad) (1905 – 1928), which happened to be years of very dramatic historical cataclysms, are still remembered as one of the most bright and efficient in its history.

In the office of director, Glazunov did not compose much, doing all he could for proper functioning of the Conservatoire. Not only did he know every student by name, but also all of their examination programs, constantly attending the classes and exams. After 1917, he had to deal with matters of heating, food allowances for students and professors, and to 'extort' funds for maintenance of the institution from the government.

The peak of Glazunov’s composing was reached in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was then that he created his ballets of astounding beauty (Raymonda, 1897, Les ruses d’amour, 1898, and The Seasons, 1899), his Fifth (1895), Sixth (1896), Seventh (1902), and Eighth (1906) Symphonies, the famous violin concerto (1904), both piano sonatas, and his best string quartets. In these years, the most fruitful for him, he composes much, but he also constantly conducts, reads lectures at the Conservatoire, and is engaged in public activity.

Glazunov died in 1936 in Paris, where he stayed from 1928 ‘on leave’ off his office as Director of Leningrad Conservatoire by permission of the Soviet Government (being in fact an émigré). He died after a long and painful illness, having left a colossal heritage of compositions comprising eight symphonies, an immense number of orchestral overtures and fantasias, ballets, works for choir and for choir and orchestra, instrumental concertos, seven string quartets, and numerous ensembles and piano pieces.

He always went his own way in music. Being Rimsky-Korsakov’s close friend and follower, Glazunov had as well a sincere liking for his “Moscow opposition׆, i.e. Tchaikovsky and Taneyev. His creative work lacks search for new ways in music so typical for the early 20th century, and might seem to be stuck in time. He always remained loyal to the ideals of his musical youth – romantic excitement, exultant air, liveliness.

His compositions seemed obsolete to young contemporaries like Prokofiev and Shostakovich. His composing style looked eclectic, as Glazunov absorbed nearly all of the best things in Russian music of those days that surrounded him. He borrowed commitment to Russian folklore from Balakirev, and he had a lot in common with Rimsky–Korsakov, affinity to colorful and virtuoso orchestration in the first place. The epic beginning of many works of Glazunov reminds the best pages of Borodin’s works. He shared Tchaikovsky’s lyrical attitude, and of course, Taneyev’s commitment to detailed polyphonic development.

Glazunov always tried to achieve a synthesis of what he valued in Russian music. He succeeded in elaborating his own creative style, probably not without certain traits of academism, but possessing a high inner integrity. His compositions are nearly always sanguine and optimistic in their musical images, bright in color, clear in form, and diverse in harmony. They are always works of a true master, a composer for whom Beauty was the main criterion of creative achievement.

Vocal music was not a favorite genre of Alexander Glazunov. Just over thirty songs, including those of his youth period, but most of all his dislike of opera, indicate that the composer had no interest in writing for voice. The core and bulk of his heritage is instrumental music. Glazunov's immense intellect was inclined to exploration of ‘pure’ genres such as symphony, quartet, instrumental concertos, and ballet music.

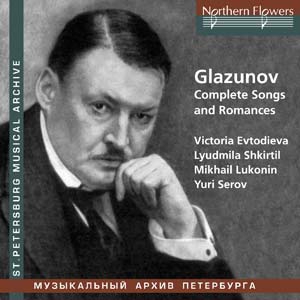

Romances and songs of Alexander Constantinovich Glazunov are released on CDs for the first time. We selected 29 of 31 finished compositions. The remaining two pieces of his young age (to Lermontov’s poems “As Soon As The Night With Its Veil” and “No, It's Not You I Love So Ardently”) were left out for one clear reason. They look much less uninfluenced than other songs of the early period of composing. The vocal heritage of Glazunov is still an under-explored stratum of Russian music, and it is to be hoped that this compact disk will find its insightful and attentive listener.

Performer’s remarks

From Hafiz and The Belle, both to words by Pushkin, open the program. These are already quite mature pieces of music. By that time, Glazunov was already author of two symphonies and several orchestral opuses, quartets, and instrumental music. While the first of the two songs is wholly integral and very laconic in its form and tools selected (curious are its resilient 'empty' intervals hinting at the Oriental color of the poem), The Belle openly displays the intention to sophisticate the composing language. Unexpected modulations, and abundant minor ‘details’ in the piano accompaniment indicate laborious search in the art of songwriting. Interestingly, the same Pushkin’s poem attracted the attention of Rimsky–Korsakov seven years after.

The two songs to words by A.S. Pushkin (op. 27) are among the best pages of Glazunov’s vocal music. Why Do I Not Hear The Roar Of Joy? strikes you with sophisticated contrivances in harmony. The composer chose to stylize the piano part to resemble ancient harp. The archaic scales used also add to the ‘Bacchic’ color. As to Oriental Romanza (“My Blood Is Burning With Desire… ”), it is really a soft sensation in Russian music. Glinka's famous masterpiece to the same verses - resiliently rhythmic, excited, and dashing – was totally revised musically. The young composer plunged the small Pushkin poem into an atmosphere of Oriental comfort and love bliss, emphasized its erotic shades, and probably came nearer to the truth in his musical concept of the poem.

The twelve songs, op. 59 and op. 60, written in 1898 are undoubtedly the most interesting in Glazunov’s vocal heritage. The point here is not that it is virtually the only case when the mature composer addressed the lyrical vocal genre (a few later songs, scattered in time and stylistics, should hardly be considered); what is important is the especially high quality of the pieces, and a special historical context that called these opuses into being.

Rimsky–Korsakov, whose artistic and personal (the latter was even greater) impression on Glazunov is hard to overestimate, wrote over 50 songs in the summer of 1897. He created them after many years of crisis in this genre. There were times when he composed several songs a day, comprehending a new style of vocal composing based on melodized recitative narration, and thus preparing for creation of Czar’s Bride. The poetical substrate of those songs was mainly poems by Pushkin, Ap. Maikov, and Alexey Tolstoy. Without any doubt, the creative quest of his senior friend urged Glazunov to resume working on vocal miniatures, also because Rimsky–Korsakov had frequently reproached Glazunov for lack of liking for vocal music, and strongly advised him to start writing songs.

Glazunov did not ‘argue’ with Rimsky–Korsakov, using the same literary texts (although a few similar intonations (sometimes almost ‘quotations’) indicate an extremely powerful influence of Rimsky–Korsakov’s vocal style on Glazunov in the late 1890’s). Still, borrowing much from him, Glazunov as always advances his own way. What is really the most important in these opuses is a new great lyrical warmness and special cordiality. Some of the songs (When Your Eyes, Delia, Desire) suggest that we take a new look not only at Glazunov’s vocal heritage, but also at his style of composing in general. Deep tenderness, implied passion, elegiac attitude, and soft rhythms of the tunes reveal the author of Raymonda, and show us some of the inner world of the ever-reserved Alexander Constantinovich.

Addressing home genres typical for Glazunov’s stylistics can also be seen in Opuses 59 and 60. The composer uses the forms of waltz (Delia), mazurka (The Grace Cup), elegy (Desire), and barcarole (Near The Land Where Golden Venice Reigns). As in his other compositions, Glazunov is masterful experimenting with ancient scales, for which purpose, most suitable were the poems by Korinfsky (from Petrarca: We Used To Live At The Foot Of A Hill and If You Want To Love). All the twelve songs of 1898 are strongly distinctive, unlike each other, carefully polished, full of vocal splendor, and represent an excellent recital material, which is still so scarcely used in the performing practice.

Dominating in the duo Hey You, My Free Song! are the tones of a Russian drawling folk song, but an undeniable influence of the amazing Six Duos, op. 46 of Peter Tchaikovsky is also felt.

The arrangement of the Russian traditional song Masha Is Told Not To Cross The River ndicates the composer’s deep knowledge of Russian background voice polyphony. It is one of the best samples of this style in Russian vocal music.

The two 1916 compositions are Glazunov’s last efforts in vocal music. The gloomy colors of Shakespeare’s Sonnet LXVI are implemented in a lapidary and somewhat ascetic musical form. The piece definitely contains a special inner strain. Nina’s Song from the music to Lermontov’s The Masquerade is styled as a ‘fierce’ home romance, and remains one of the most popular and performable vocal pieces by the composer up to this day.

The vocal compositions of Alexander Glazunov as a young man are very curious for several reasons. He paid much more attention to songs in the initial years of his composing than in later periods; the earlier pieces allow to trace in detail the development (rapid development!) of the composer's abilities; the texts of the poems tell us much about the outlook of young Glazunov, and his progress as personality. The composer always kept plenty of books at home, and his passion for reading was a life–long one. This is the source of his many selections from Heine’s translations, and of profound affinity to Pushkin and Lermontov as literary ‘idols’ of Russia’s educated society. Taken on the whole, the initial vocal experiments of Glazunov are very interesting, melodic, and written simply and cordially, after the fashion of the 19th century Russian home romances. The somewhat pathetic, dramatic, and brisk Stifling! ; the exquisite Spanish Romanza (again arguing over one and the same text by Pushkin, but this time, with Dargomyzhsky's masterpiece); Lermontov's Whenever I Hear Your Voice, a 'lovely' one with a broad vocal part amplitude; and My Songs Are Venomous… being nearly an imitation of Borodin. (For his own song to the same text named “My Songs Are Full Of Poison”, Borodin had translated Heine’s poem himself).

The five songs of Opus 4 are selected from the young man’s compositions of 1881–1885. They differ much in the expressive power of images and in stylistics. The choice of the poetical base is representative: Koltsov’s poem alone, a subtle and airy one, may be referred to as high poetry. The rest are translations. Two of these are from Heine (the Russian translation by Dobrolyubov is very much ‘russified’), and two are traditional (Arab and Spanish) texts. Still, the composer was successful in many pages of these early songs. Spanish Song and Arab Melody deserve a closest attention of performers. In full compliance with the abundant Russian tradition of ‘orientalism’, they have catching tunes provided with all appropriate ‘ethnic’ intonations, characteristic resilient rhythms, and passionate narrative ‘exclamations’; in all fairness, they should prove successful when played onstage. To Your Snow–White Bosom and When I Look Into Your Eyes lack such striking individuality, but are interesting because of their fruitful research in harmony and format. The Nightingale is somewhat detached in this cycle: young Alexander surely knew Rimsky–Korsakov’s borrowing of that same poem of Koltsov, and largely he simply copied his teacher. The two pieces are too consonant in their atmosphere, and in their distribution of the literary material within the music’s time frame.

|

|

1. From Hafiz. Words by A. Pushkin

Don’t be lured by warlike glory, O young and handsome lad! Don’t rush into a bloody battle With a horde of Karabakh! I know, Death will not have you; Azrail will mark your beauty Amidst battle swords — And you will be spared! But I fear, in all these battles You will lose forever Your timid modesty of movements, Your charm of languor and shyness! 3. Восточный романс. Слова А. Пушкина В крови горит огонь желанья, Душа тобой уязвлена, Лобзай меня — твои лобзанья Мне слаще мирра и вина. Склонись ко мне главою нежной, И да почию безмятежной, Пока дохнёт весёлый день И двигнется ночная тень. 5. Муза. Слова А. Пушкина В младенчестве моём она меня любила И семиствольную цевницу мне вручила; Она внимала мне с улыбкой, и слегка По звонким скважинам пустого тростника Уже наигрывал я слабыми перстами И гимны важные, внушённые богами, И песни мирные фригийских пастухов. С утра до вечера в немой тени дубов Прилежно я внимал урокам девы тайной; И, радуя меня наградою случайной, Откинув локоны от милого чела, Сама из рук моих свирель она брала: Тростник был оживлён божественным дыханьем И сердце наполнял святым очарованьем. 7. Из Петрарки (Когда твои глаза…) Перевод Ап. Коринфского Когда твои глаза встречаются с моими, Случается порой, что влага жгучих слёз Готова в них блеснуть, и ропот тайных грёз Мне сердце леденит нежданно вместе с ними. Ты улыбаешься очами неземными, Любуюсь я тобой, забыв раскаты гроз; И аромат любви, благоуханней роз Мне веет на душу мечтами золотыми. Холодною тоской опять я полон весь: Не светят для меня твои глаза — созвездья роковые. И тёмен для меня лучистый свет дневной. Тоска моя летит на крыльях за тобой. Зачем ты унесла мечты мои живые! 9. Делия Слова А. Пушкина Ты ль передо мною, Делия моя? Разлучён с тобою — Сколько плакал я! Ты ль передо мною, Или сон мечтою Обольстил меня? Ты узнала ль друга? Он не то, что был; Но тебя, подруга! Всё ж не позабыл — И твердит унылый: „Я любим ли милой, Как бывало был?“ 11. Застольная песня. Слова А. Пушкина Кубок янтарный Полон давно — Пеной угарной Блещет вино; Света дороже Сердцу оно; Но за кого же Выпью вино? Пейте за славу, Славы друзья! Бранной забавы Любить нельзя. Это веселье Не веселит Дружбы похмелье Грома бежит. Жители неба, Феба жрецы, Здравие Феба Пейте, певцы! Резвой Камены Ласки — беда; Ток Ипокрены Други, вода. Пейте за радость Юной любви, Скроется младость, Дети мои… Кубок янтарный Полон давно. Я, благодарный — Пью за вино! 13. Нереида Слова А. Пушкина реди зелёных волн, лобзающих Тавриду, На утренней заре я видел нереиду. Сокрытый меж дерев, едва я смел дохнуть: Над ясной влагою полубогиня грудь Младую, белую как лебедь, воздымала И пену из власов струёю выжимала 15. Жизнь ещё передо мною… Слова А. Майкова Жизнь ещё передо мною Вся в видениях и звуках, Точно город дальний утром, Полный звона, полный блеска. Все минувшие страданья Вспоминаю я с восторгом, Как ступени, по которым Восходил я к светлой цели. 17. Эх ты, песня, песня вольная! Слова П. Северского Эх ты, песня, песня вольная! Словно пташечка поднебесная По полям, лугам, по дубравушкам Ты летишь себе, беззаботная. И с тобой душа без тоски живёт, Сердце пылкое бьётся радостно. Красна девица горе мыкает. Добрый молодец счастьем тешиться. 19. 66–й сонет Шекспира Зову я смерть… Перевод А. Кремлёва Зову я смерть, покой моих скорбей; Я вижу, что бедняк назначен Не к радости, а к горю всех людей, Долг верности чистейший в них утрачен; Честь ложно недостойным воздана, Достоинство унижено обидно, И чистота души развращена. Хромая власть сковала дух постыдно, Заставила искусство замолчать; Невежда, как учёный, правит знаньем, И глупостью все скромность стали звать; Добро в плену у зла: таким сознаньем Измученный, оставил землю я, Когда б не здесь была любовь моя! 21. Душно без счастья и воли… Слова Г. Гейне, перевод Н. Некрасова Душно! Без счастья и воли Ночь бесконечно длинна. Буря бы глянула, что ли? Чаша с краями полна! Грянь над пучиною моря, В поле, в лесу засвищи, Чашу вселенского горя Всю расплещи!… 23. Слышу ли голос твой… Слова М. Лермонтова Слышу ли голос твой Звонкий и ласковый, Как птичка в клетке Сердце запрыгает; Встречу ль глаза твои Лазурно–глубокие, Душа им на встречу Из груди просится, И как-то весело И хочется плакать, И как на шею бы Тебе я кинулся. 25. Ко груди твоей белоснежной… Слова Г. Гейне, перевод Н. Добролюбова Ко груди твоей белоснежной Я голову тихо склонял И что тебе сердце волнует В биенье его угадал. Чу! В город вступают гусары, Нам слышен их музыки звук. И завтра меня ты покинешь, Мой милый, прекрасный мой друг. Пусть завтра меня ты покинешь, Зато ты сегодня моя! Сегодня в объятиях милой Вдвойне хочу счастлив быть я. 27. Когда гляжу тебе в глаза… Слова Г. Гейне, перевод М. Михайлова Когда гляжу тебе в глаза, Стихает на сердце гроза; Когда в уста тебя целую, Душою верю в жизнь иную. Когда склонюсь на грудь твою, — Не на земле я, а в раю! Скажи "люблю" — и сам не знаю, Отчего так грустно зарыдаю! |

2. The Belle. Words by A. Pushkin

She is all harmony, all wonder, She’s all above the world and passion; She is reposed diffidently In her magnificent beauty; She glances around her Seeing no rivals and no friends; And the pale circle of our belles All fades away in her beams. Куда бы ты не поспешал, Хоть на любовное свиданье, Какое б в сердце не питал Ты сокровенное мечтанье, — Но, встретясь с ней, смущённый, ты Вдруг остановишься невольно, Благоговея богомольно Перед святыней красоты. 4. Песня. Слова А. Пушкина Что смолкнул веселия глас? Раздайтесь, вакхальны припевы! Да здравствуют нежные девы И юные жёны, любившие нас! Полнее стакан наливайте! На звонкое дно В густое вино Заветные кольца бросайте! Подымем стаканы, содвинем их разом! Да здравствуют музы, да здравствует разум! Ты, солнце святое, гори! Как эта лампада бледнеет Пред ясным восходом зари, Так ложная мудрость мерцает и тлеет Пред солнцем бессмертным ума. Да здравствует солнце, да скроется тьма! 6. Из Петрарки (Мы жили у подножия холмов…) Перевод Ап. Коринфского Жили мы у подножья холмов У цветущего горного склона, Где родилась земная мадонна, Что пленила любимца богов. Посреди ароматных лугов Мы не знали неволи закона. Был над нами шатёр небосклона, А вокруг нас — гирлянды цветов. Но, пленённый Лаурой, поэт Нас поймал в зеленеющем поле. В час, когда загорался рассвет. Жизнь его не милей нашей доли, Любит он, позабыв целый свет, А в любви ни покоя, ни воли. 8. Если хочешь любить… Слова Ап. Коринфского Если хочешь любить, — приучайся страдать, Нет любви без страданья на свете. За блаженство минутного счастья в ответе Вечность — горя бессмертного мать. Если жаждешь страданья — терпенью учись; Человек терпелив по природе, Только надо забыть о порывах к свободе И с земли не стремиться в небесную высь. Если любишь страданья и терпишь любя, Не подумай, что жертву приносишь собою. Доброй волей идёшь ты тернистой тропою, Ты страданьем любви услаждаешь себя. 10. Всё серебряное небо… Слова А. Майкова Всё серебряное небо! Всё серебряное море! Тёплой влагой воздух полон. Тишина такая в мире, Как в душе твоей бывает После слёз, когда, о Нина, Сердце кроткое осилит Страстью поднятую бурю, И на бледные ланиты Уж готов взойти румянец, И в очах мерцает тихий Свет надежды и прощенья. 12. Желание Слова А. Пушкина Медлительно влекутся дни мои, И каждый миг в унылом сердце множит Все горести несчастливой любви И тяжкое безумие тревожит. Но я молчу; не слышен ропот мой; Я слёзы лью; мне слёзы утешенье; Моя душа, пленённая тоской, В них горькое находит наслажденье. О жизни час! лети, не жаль тебя, Исчезни в тьме, пустое привиденье; Мне дорого любви моей мученье — Пускай умру, но пусть умру любя! 14. Сновидение Слова А. Пушкина Недавно, обольщён прелестным сновиденьем, В венце сияющем, царём я зрел себя; Мечталось, я любил тебя — И сердце билось наслажденьем. Я страсть у ног твоих в восторгах изъяснял, Мечты! ах! отчего вы счастья не продлили? Но боги не всего теперь меня лишили: Я только — царство потерял. 16. Близ мест, где царствует Венеция златая… Слова А. Пушкина Близ мест, где царствует Венеция златая, Один, ночной гребец, гондолой управляя, При свете Веспера по взморию плывёт, Ринальда, Гольфреда, Эрминию поёт. Он любит песнь свою, поёт он для забавы, Без дальных умыслов; не ведает ни славы, Ни страха, ни надежд, и, тихой музы полн, Умеет услаждать свой путь над бездной волн. На море жизненном, где бури так жестоко Преследуют во мгле мой парус одинокий, Как он, без отзыва утешно я пою И тайные стихи обдумывать люблю. 18. Не велят Маше за реченьку ходить… Слова русской народной песни Не велят Маше за реченьку ходить, Не велят Маше молодчика любить. Я молодчик то, любитель дорогой, Он не чувствует любови никакой. Какова любовь на свете горюча: Стоит Машенька заплаканы глаза. 20. Романс Нины Слова М. Лермонтова Когда печаль слезой невольной Промчится по глазам твоим, Мне видеть и понять не больно, Что ты несчастлива с другим. Незримый червь незримо гложет Жизнь беззащитную твою, И что ж? Я рад, что он не может Тебя любить, как я люблю. Но если счастие случайно Блеснёт в лучах твоих очей, Тогда я мучусь горько, тайно, И целый ад в груди моей. 22. Испанский романс Слова А. Пушкина Ночной зефир Струит эфир. Шумит, бежит Гвадалквивир. Вот взошла луна златая, Тише… чу… гитары звон… Вот испанка молодая Оперлася на балкон. Ночной зефир Струит эфир. Шумит, бежит Гвадалквивир. Скинь мантилью, ангел милый, И явись, как яркий день! Сквозь чугунные перилы Ножку дивную продень. Ночной зефир Струит эфир. Шумит, бежит Гвадалквивир. 24. Песни мои ядовиты… Слова Г. Гейне, перевод Н. Добролюбова Песни мои ядовиты. Как же в них яду не быть? Цвет моей жизни отравой Ты облила мне, мой друг! Песни мои ядовиты. Как же в них яду не быть? Множество змей в моём сердце Да ещё ты, мой милый друг. 26. Соловей Слова А. Кольцова Пленившись розой соловей, И день и ночь поёт над ней, Но роза молча песням внемлет… Невинный сон её объемлет… Не лире так певец иной Поёт для девы молодой; Он страстью пламенной сгорает, А дева милая не знает, Кому поёт он? Отчего? Печальны песни так его. 28. Арабская мелодия Слова народной песни Я не в силах сносить дольше мук любви, Уж сердце моё заполонено. Кто может мне его из плена возвратить, Тот от меня заслужит благодарность вечную, Тот для меня лучший в свете друг. О сжалься, сжалься над ним, Над несчастным сердцем, О ты, газель моя, ты ведь так прекрасна. О сжалься, сжалься надо мной, Ведь я твой раб, твой раб покорный. Ты одна можешь утолить мои страданья. 29. Испанская песня Слова народной песни Сгони ты, о, милая, песнью своею Тоску с моего измученного сердца. Пой свои песни, пой их нежней. Чаруй меня, милая, песнью своею, Пой до тех пор их, о, жизнь моя, Пока не убаюкаешь меня Ты в сладкую дремоту. Малага! О чудный край, прости навсегда, Прости тот край, Где жил я так счастливо и мирно. О прости же и ты, моя милая, И с тобой я расстанусь. И не будет мне больше покою не свете, Смерть лишь одна принесёт Мне желанный покой! Пускай раздаётся нежней твоя песня, Пусть струны гитарные звонче бряцают, Чем прежде! Знай, моя милая, Что от звуков гитары все боли, Все страданья утихают. |