CDs

NF/PMA 99109

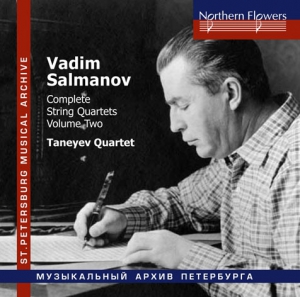

Vadim Nikolaevich Salmanov (1912-1978)

Complete String Quartets

Volume 2

String Quartet No.4 (1963)

1. Allegro non troppo 3:37

2. Allegro 2:53

3. Adagio 5:56

4. Allegro molto 3:40

String Quartet No.5 (1968)

5. Moderato con moto 5:47

6. Presto 3:48

7. Andante parlando 6:16

8. Allegro vivace 2:18

String Quartet No.6 (1971)

9. Andante semplice 7:28

10. Allegro con brio 3:27

11. Andante espressivo 5:46

12. Allegro vivace 4:06

Total Time: 54:01

The S.I. Taneyev Quartet

Vladimir Ovcharek, violin

Grigory Lutzky, violin

Vissarion Solovyev, viola

Josef Levinzon, cello

Recorded by the St.Petersburg Recording Studio: Quartet No.6 (1966), Quartet No.6 (1980)

Sound supervision: Gerkhard Tzess

Recorded by the House of St.Petersburg Composers: Quartet ¹5 (1969)

Sound supervision: Mikhail Kustov

Text: Lyudmila Mikheyeva & Rein Laul

English text: Sergei Suslov

Design: Anastasiya Evmenova & Oleg Fakhrutdinov

VADIM SALMANOV AND HIS STRING QUARTETS

Vadim Nikolaevich Salmanov, an outstanding Russian composer, is among the representatives of the Petersburg/Leningrad school of composing who made a material contribution to the development of Russian music of the Soviet period. Yevgeny Mravinsky wrote about him, “A remarkable composer, a sensitive teacher, a man of outstanding scholarship, he left a bright trace in Soviet musical art… Evaluating, from the height of my years, the landmarks where my destiny brought me close to the composer’s music born in my sight, I can say confidently that Salmanov’s heritage is a vibrating evidence of the epoch that brought him forth. Organically combined in him are definite features of up-to-date musical language – and freshness, simplicity of utterance, caprice, multi-layered concepts– and a true harmony in the use of the instruments to implement the concept… Salmanov’s music is absolutely free of speculation or schematism. Sincerity of live emotion is always heard in it, and an inspired flight of fantasy. It is filled with high glow of struggle, and many of its pages breathe with passionate excitement. And still another quality of this music deserves special mentioning. It is nobleness of utterance… Salmanov’s music is truly Russian both in its spirit and its ethical focus. It has rigor and manliness. And I think, I must mention Salmanov’s innovative interpretation of Russian classical traditions. In this respect, I would mention the names of Taneyev, Glazunov, Prokofiev, and of course Shostakovich.”

Salmanov addressed many genres, except for musical theater. His heritage includes symphonies and symphonic suites, chamber instrumental ensembles, vocal cycles and choruses, piano pieces, and pieces for other instruments. His Fair Swan, concerto for choir a cappella to folk lyrics, and The Twelve, oratorio poem for choir and symphony orchestra to verses by Blok, are real pearls of Russian music.

Vadim Nikolaevich Salmanov was born in St. Petersburg, into an intellectual and well-to-do family, on October 22 (November 4) 1912. His father Nikolai Germanovich Salmanov, a metals engineer by education, was a fairly good pianist, a pupil of the famous Yesipova. The information on his mother Yelena Alexandrovna, nee von Fricken, is very scarce; she left the family soon, and little Vadim was taken into custody by her younger sister Olga who fully devoted herself to her nephew.

The boy’s early impressions were related to his father’s excellent piano playing, to the sounds of music of Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff. There was a fine music library in the home, and musical parties attracted remarkable performers, in particular Medea Figner, the famous prima donna of the Mariinsky Theater. Wishing to turn his son to music, father became his first teacher of piano. However, his insistence and demands for the five-year-old boy, excessive in other relatives’ opinion, resulted in the boy’s hatred towards the piano; he even attempted to set it on fire once. To show his protest to father who schooled him on the best examples of classical music, he tinkled pop foxtrots, and that made father furious. He used to say to his loving aunt, “Wait, I’ll grow old, I’ll sell this piano and get married!”

When the time came to go to school, Vadim was sent to one of the best in town, the former Tenishev School, which had an excellent cast of teachers and high level of education. Although those were the post-Revolution times, with anarchy ruling in education and the so-called unified labor school unable to provide real knowledge, Salmanov gained brilliant diversified knowledge in that school, in particular flawless French and knowledge of English and German. Apart from studying at the Tenishev School, Salmanov had a full course of music theory and harmony read by F. Akimenko, and then by S. Barmotin who were alumni of Rimsky-Korsakov and Lyadov. He continued his piano lessons with Professor O. Kalantarova, a pupil of Yesipova. The boy was preparing to enter the conservatory, but Nikolai Germanovich who had long been severely ill died in the year when he finished school. In 1930 Salmanov moved from the city’s prestigious district to Gorokhovaya Street, to live with aunt and mother, and found a job of mechanic’s apprentice in a factory. One year after he found another job related to hydrogeology, and entered the evening department of the geological prospecting college. He spent a few years in extended field traveling, mostly to the north. It was then that his passion for photography began, to last throughout his life. This passion was so strong that Salmanov later said jokingly that photography was his occupation, and music was just a hobby.

The decision to change his life came to him in 1933, after a concert of Emil Gilels that made a colossal impression on the young man. Salmanov resumed his studies of musical subjects, and in 1936 he entered the Leningrad Conservatory to study in the composition class with Professor M. F. Gnessin, a talented teacher who kept the traditions of Rimsky-Korsakov. He had to combine studying at the conservatory with work, for his scholarship was not enough to live on. Luckily, he found a job suiting his vocation; a second-year student, he was so good at instrument knowledge that they let him teach this subject at the school of the Conservatory. Besides, he became a concert master in the in the choral and vocal amateur of the Leningrad Institute of Railway Engineers. It may be supposed that continuous direct work with vocalists and choir singers, albeit not much professional, promoted love for choral singing and vocal genres in him, thus originating future beautiful opuses.

Salmanov was passing the graduation exams when the Great Patriotic War broke out. Right after receiving the diploma, he was enlisted to the army. Fortunately, his activity in the war was reduced to service in the musicians’ platoon of the Birsk military college near Ufa, where he played helicon according to a preserved photo, but probably also taught musical subjects to other students. Gnessin who took ardent care for his talented student did his best to get him out of that service, but the professor’s solicitudes only succeeded in 1945 when the war was near its end. Gnessin called Salmanov to Moscow and employed him as teacher in his (named after the Gnessins) Institute of Music. Salmanov taught there until 1949.

At that time, some event happened to determine the rest of his life. As early as in the pre-war years, he liked the company of his relatives on the mother’s side, his male and female cousins. In the summer of 1939, a large company spent time in Baranovo village, on the shore of Lake Seliger. Once, in a storm during a boat ride, the young people went ashore and found a shelter in an old nailed-up church. Abandoned sacred articles were scattered there in disarray. They got naughty and decided to “play a wedding.” Vadim was the groom, and his 14-year-old cousin Svetlana was the bride. They held the bridal crowns over the newly-weds, and made an entry in the book of records. Probably that instant sank into her heart, or maybe she agreed to the wedding because she had long been in love with her grown-up cousin in a childish way. Anyway, they met again in Moscow, where Svetlana studied in an institute. As to Salmanov, he was not free: in the wartime he had got married, thoughtlessly and too rapidly. Some time was needed to get the consent to divorce from his wife. Meanwhile, Svetlana obtained a transfer to the Institute of Cinema Engineers in Leningrad, and Salmanov followed her to Leningrad in 1949. He managed to get a job of teacher in the school of the conservatory where he taught once when still a student. Two years later, in 1951, he became a Conservatory teacher. The long-awaited divorce was obtained too. The Union of Composers, a member of which he became in 1953, managed granting him a personal apartment. And soon he wrote his first large works: First Symphony, Lyrical Pages for violin with piano, Slavic Merry-Go-Round for symphony orchestra, symphonic suite Poetical Pictures after Andersen’s tales, and songs to Yesenin’s verses. The Twelve, an oratorio poem after Blok, was the acme of those years.

His life went by steadily: Salmanov taught students, and spent the summer vacations in a House of Creativity, usually in his beloved North, in Sortavala on the shore of Lake Onega. He brought rich harvests of mushrooms from there, and surely photographs. His wife shared his passion for photography, she selected frames together with him, and prepared reagents – Salmanov believed that absolutely everything should be done with own hands. He was preoccupied with photography not only in vacation time, though. When in Leningrad, Salmanov took advantage of every free sunny day to go “photo hunting.” There are hundreds of splendid views of the city in his archive, such as bridge gratings, but first and foremost St. Isaac’s Cathedral at every angle, in every detail, and variously illuminated.

In 1959 he completed the Second Symphony, then the choruses, and in 1962, the “Children’s Symphony” probably related to the birth of his only son. 1964 saw his only composition for musical theater, the one-act Man after E. Mieželaitis, and besides, choruses to verses by Yesenin and the Violin Concerto. In 1965, Vadim Salmanov was awarded the title of Professor. Two years later, he wrote one of the best compositions, The Fair Swan, a choral concerto to folk lyrics, and new chamber vocal and instrumental compositions, to which the composer had a special disposition.

So the years went by. His Fourth Symphony, the last one, was written in 1976. By that time, the composer had been feeling more and more uneasy in the conservatory. Senior colleagues with whom he started his teaching career were leaving. He felt that his stringent requirements and his nonconformism are disliked by younger members of the faculty, with whom he was losing common ground more and more. Salmanov, with his intellectual refinement, knowledge of languages, general education rather unusual for a musician, broad erudition, and above all his keen and extremely biting, sarcastic wit, felt a stranger among people of another generation and another education and outlook.

Little by little, he was getting inclined to quit the conservatory. Vadim Nikolaevich did so in 1976. Friends tried in every way to mitigate the abrupt change in his life. His former student Igor Luchenok, chairman of the Belorussian Union of Composers, arranged for a tour in Minsk and other cities of Belorussia. Upon his return to Leningrad, he wrote new music, mainly to verses by Nikolai Rubtsov, a poet especially close to Salmanov in those years. It was a cycle of songs titled In Minutes of Music, Three Male Choruses, and cycle of songs My Russia. Besides, he wrote the Third Sonata for violin and piano in 1977.

Vadim Salmanov died in Leningrad on February 27, 1978.

L. Mikheyeva

The chamber instrumental music of Vadim Nikolaevich Salmanov holds a key place in his heritage. Especially remarkable are the six string quartets, the Fourth String Quartet written in 1963 having a special position among them. At that time, Salmanov actively addressed dodecaphony, and that when dodecaphony was all but banned in the Soviet Union. The Fourth Quartet became perhaps the most remarkable example of application of this technique. This writer remembers the delight, with which the opus was received at its demonstration in Leningrad’s Union of Composers in the autumn of 1963. I can still hear the words of musicologist Yuri Weinkop, “Today we celebrate!”

The Fourth Quarter was far from the first time that Salmanov addressed dodecaphony, and demonstrates a virtuoso grasp of it. In his practice, Salmanov left a noticeable personal mark in the composing technique of dodecaphony, but a modest person as he was, he did not overestimate his knowledge in the general theory. He used to readdress questions of such kind to me if asked in my presence (“You should better ask Laul about that”), as I was already specialized in this subject and later defended a thesis on Schoenberg’s music. Actually, Salmanov himself was very far from naïve dodecaphony and preferred free use of repeated sounds and sound groups, which absolutely does not contradict the strictest rules of the technique.

While Stravinsky emphasized that he accepted dodecaphony not in Schoenberg’s but in Webern’s version, Salmanov adopted it just in Schoenberg’s version, as L. N. Raben justly remarked. But Salmanov’s music is so far from Schoenberg’s music! Tragic pathos and pessimistic reflection are unfamiliar to it; it is brimming with buoyancy.

The main theme of the first movement of the Fourth Quartet is representative in this sense. In its nature it reminds the brightest pages of Salmanov’s music, such as Children’s Symphony. At the same time it fully complies with the strictest rules of dodecaphony; the parallel flow of the basic series in two end parts is arranged so that a bright G major can be clearly heard, with the entire two-voice texture quite fitting in the system’s rules. It is just a wonder how many expressive melodies Salmanov managed to derive from one series! The main theme is repeated six times and is determinant for the first movement. The second theme only adds a dramatic element to the music, but since it is not repeated, it cannot be considered as a subsidiary theme; in fact there is no sonata form in the movement.

The cheerful first movement does not represent the entire content of the quartet. All other movements based on other series present other spheres of imagery. The second movement, in place of a scherzo, is restless and harsh, and represents “a world of forces alien to human happiness.” The quartet’s Adagio, a passacaglia treated very freely, displays lyrical expression and philosophical profoundness. And the outrageous finale based on a “clattering” triplet motif (it could already be heard in the first movement) still ends in the bright theme from the quartet’s first movement.

The Fifth Quartet is the last of Salmanov’s dodecaphonic quartets. Its dodecaphony is much less strict. The first movement opens in a motif that may be described as a motif of appeal, followed by chords and passages using the material of the basic series, which is thus quite disguised. It is not until the twelfth bar that it is stated in a melodic firm, of an epic nature at first. Next, it is joined by a number of similar melodic structures and inner voices. As a result, a certain meaningful conversation starts between them, where both the appeal motif and the introduction passages sound as “valid arguments.”

The second movement is a fantastic scherzo in a duple meter (as in Schumann’s Second Symphony) and in an almost incessant motion of semiquavers. The fast meandering “serpentine lines” sound now mysteriously, then bitterly; they create a fantastic atmosphere somewhat reminding the third movement of Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite. The slow third movement is based on clusters alternating with a rigorous chorale and expressive unison tunes. This opus, as any other quartet by Salmanov, has many harsh harmonies demonstrating another advantage of the composer’s music, i.e. a rich harmonic language. The fast vigorous finale is traditional for sonata-symphony cycles. This quartet has different series in all of its movements.

The last Sixth String Quartet is Salmanov’s parting with the dodecaphonic technique. By that time, he had already exhausted the serial technique abilities for himself. It cannot be said that the preceding experience had yielded no positive result: the control of the pitch organization was enhanced, the melodies became clear-cut, and the harmonies more expressive. The Sixth Quartet, like the two preceding ones, consists of four movements united in a cycle to the same pattern: the first movement is in a moderate tempo, the second one is fast, the third one is slow and the lyrical center, while the fourth one is a traditional finale possibly with a reminiscence of the quartet’s beginning.

The quartet’s first movement echoes the first movement of the dodecaphonic Fifth Quartet. It opens in an epic narrative theme. It may seem at first that a fugue exposition is presented, but the “reply” does not quite meet the fugue canons. This will happen again and again. Salmanov generally prefers versions to exact repetitions, offering ampler abilities for development. Another recognizable feature is that the appearance of semiquavers is delayed on purpose, which noticeably animates the motion. Choral fragments appear too, with harsh chords typical for Salmanov. At the very end of the movement, a varied epic tune reappears with the viola.

The second movement is a merry cheerful scherzo in C major, slightly reminding the piece Juliet As A Young Girl from Prokofiev’s ballet. It offers many humorous effects and inventive quartet sonorities. The dancing first theme is replied by the pastoral second theme.

The third movement is abundant in interesting quartet sonorities where the top part is not always performed by the first violin. A new and more mobile tune of the first violin is strikingly catchy. As in the first movement, we have here a tremendous diversity of folk-style epic tunes. The finale is based on a large motif, which is a strong unity of two similar sub-motifs at different absolute pitches. It is extremely captivating to watch the play of ample abilities of the “resilient,” “whimsical” motif and its “adventures” in various situations. The finale’s culmination is based on a choral texture and is placed in the middle of the movement, after which, variants of the main motif reappear. And in the quartet’s final bars, we hear the epic tune from the first movement again.

Rein Laul, composer and musicologist